Last week Marie Winn, Ken Chaya and I trekked up to the New York Botanical Garden for a special tour. Daniel Atha was kind enough to show us around the herbarium and describe step-by-step how plant specimens are vouchered. It is a time-consuming process involving several people, but in the end you have a beautifully pressed specimen that can be preserved for hundreds of years.

The herbarium at the New York Botanical Garden is the largest herbarium in the Western hemisphere and the third largest in the World. The herbarium is around 100 years old and contains approximately 7 million specimens from all over the world, the oldest of which date back to the 1760s.

The first stop on our tour was Daniel's office. In earlier posts, I showed how Daniel presses plants in the field. Once in the office, he goes through each specimen to make sure they are laid out properly, so that all features can be seen. Once the specimen is dried, you cannot change the layout, so this is an important step. He also checks to make sure the number allocated to the specimen matches his notes and identification.

Daniel and Marie in Daniel's office at the New York Botanical Garden

To be dried properly, each plant specimen is pressed in a folded sheet of newspaper and sandwiched between two sheets of blotter paper and two sheets of corrugated cardboard. All the specimens collected are then stacked. Moisture moves as a vapor from the plant to the blotter to the cardboard. The stack is put on a dryer so that warm air can pass through the vents in the cardboard taking all that moisture and evaporating it into the air.

Daniel, Marie and Ken stacking specimens

Specimens are sandwiched between blotter paper and corrugated cardboard

Insects and fungi are the nemeses of an herbarium collection. They can destroy specimens in no time at all. In the photo below you can see one such critter that made its way into samples that I collected. Dermestid beetles are a group of beetles also known as carpet beetles, skin beetles, larder beetles. They are scavengers that feed on dried plant or animal tissue. They are very specific about what they feed on. Some species feed on plants, some on mammals, some on birds, etc. This species has a fondness for sunflowers, but will probably feed on other plant species as well. The black specks you see are called frass, (insect poop). The worm-like creature you see is the larvae (young) of the beetle.

Dermestid beetle feeding on my sunflower specimen

Insects and other organisms (such as fungi) are destroyed by placing the dried plant specimens in a freezer that is kept at -40C. Although some species can survive extreme temperatures, they cannot survive the sudden change from room temp to -40. All dried specimens go into this freezer for 48 hours.

-40C freezer

Herbarium speciemns throughout the United States are mounted on a standard size sheet of paper (11 1/2 x 16"). The paper is acid-free cotton rag.

Mounting paper

The collector of the specimen provides all the information to make a label. These labels include the scientific name of the species, the location where it was collected, the name of the institute that supported the collection, the name of the collector(s) and the date collected. Daniel provides all of this information to his assistant who makes the labels and enters the data into the herbarium database.

Specimen and label

The specimen then goes to the mounter. She carefully glues the specimen to the mounting paper. Also glued to the paper are the label and an envelope to hold bits of the plant that might break off. The sheet is stamped with the name of the botanical garden and it is given a bar code. Once the specimen gets photographed for the database, it gets a stamp saying "imaged". After the specimen is mounted, it gets put in the -40C freezer a second time to ensure no organisms survived.

Mounting a specimen

The final product

Items, such as fruit, that are too large to mount on the sheet get put in boxes with the same label information and bar code.

Fruit too large to be mounted

A few fresh leaves are quickly dried and preserved in silica to be available for DNA analysis. This also gets the same label information and its own unique bar code.

Tissue preserved in silica for DNA analysis

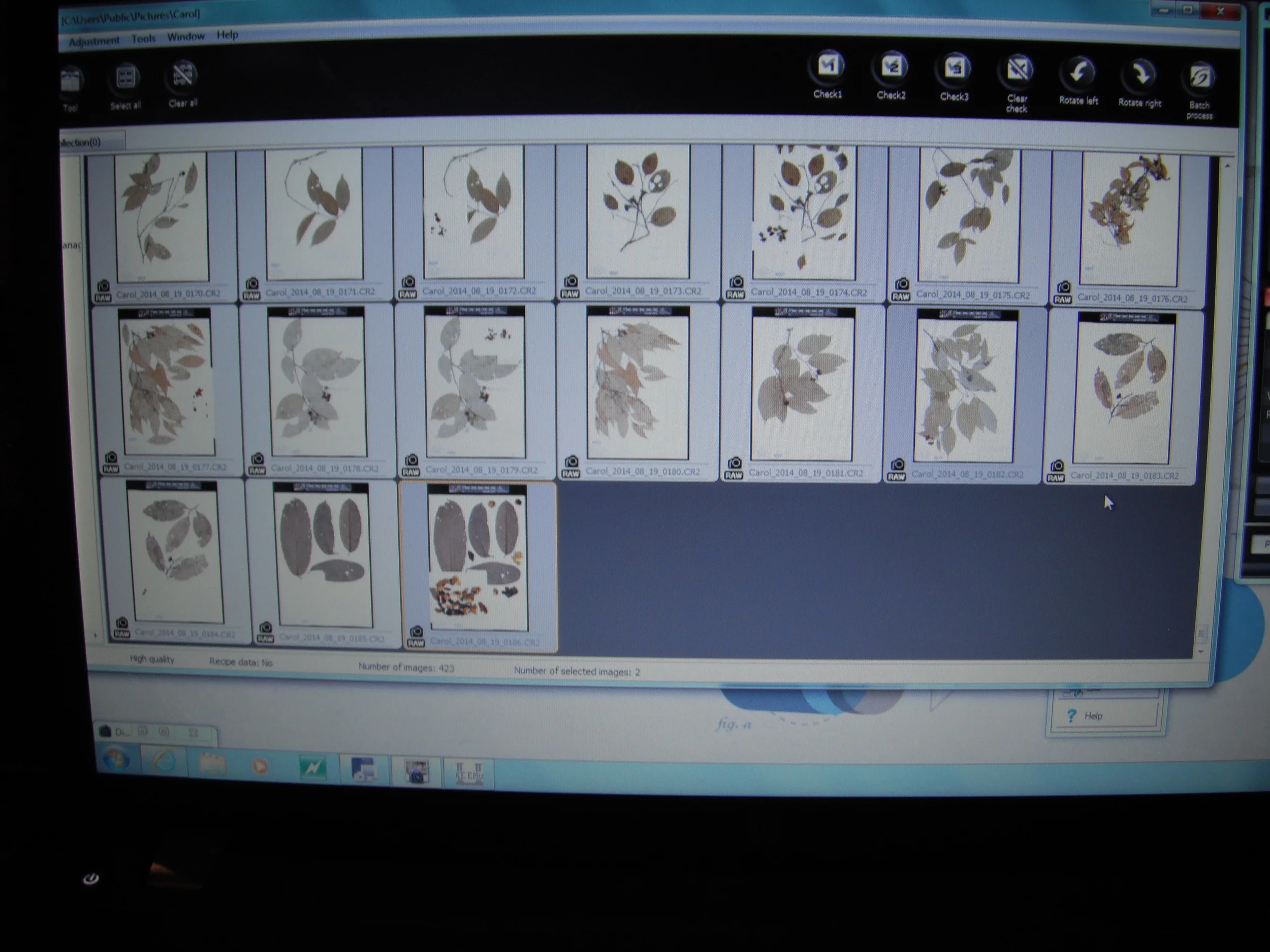

Information from each specimen is entered into the herbarium database. Also included in the database is a photo of the specimen. To produce the photo, the specimen is placed in a light box that has a camera mounted above. The photos are high resolution and researchers looking at specimens online usually can see enough detail to make a proper identification.

Preparing a specimen to be photographed

Photos of specimens to be added to database

All collectors must provide all the collection information for each specimen so that labels can be generated. Without this information, the specimen is useless. This is a time-consuming process that sometimes a collector does not get around to doing. In that case, a collection can sit on the shelves of the "cold room" for years or even decades. There are approximately 1 million specimens waiting at any given time to be processed. Garden researchers process anywhere from 10,000 to 30,000 specimens a year.

Collections stored in the cold room, waiting to be processed

Once all of the above steps are completed, the specimen finally gets filed into the herbarium cabinets.

The herbarium itself is an entire building with temperature and humidity controlled rooms. These rooms are lined with cabinets that hold the 7 million specimens. Each cabinet contains samples from a plant family from a specific part of the world.

The herbarium

Inside the cabinets, folders group the plants into genera and species.

Specimens filed by family and genus

As a final treat, Daniel ended the tour by showing us some of the oldest specimens in the collection. He showed us two from Captain Cook's first expedition. James Cook was a British explorer and navigator who made several expeditions around the globe, including the first European contact with Australia and the Hawaiian islands. These specimens were collected during his first voyage which lasted from 1768-1771.

Daniel also showed us a specimen collected by Charles Darwin during the Voyage of the Beagle, 1831-1836. Darwin was an English naturalist and geologist. We know him best for his contributions to the theory of evolution. The voyage of the Beagle lasted 5 years and went mostly around South America.

It is exciting to think that our specimens might be studied by someone interested in the Flora of Central Park two or three hundred years from now.

Specimen from Captain Cook's voyage

Specimen from Captain Cook's voyage

Some of the oldest specimens in the collection

A moss collected by Darwin